May Revolution

| May revolution | |

|---|---|

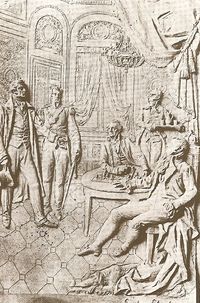

The open cabildo on May 22, 1810, by Pedro Subercaseaux |

|

| Other names | Revolución de Mayo |

| Location | Buenos Aires |

| Date | May 25, 1810 |

| Result | Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros is deposed and the Primera Junta assumes government. Other cities in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata are torn between joining the revolution or standing against it. |

| Website | Education Ministry commemorative website (Spanish) |

The May Revolution (Spanish: Revolución de Mayo) was a week-long series of revolutionary events that took place from May 18 to May 25, 1810, in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, a colony of the Spanish Empire which included the present-day nations of Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay. The consequences of these events were the ousting of Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros and the establishment of a local government, the Primera Junta (First Junta) on May 25. These events are commemorated in Argentina as "May Week" (Spanish: Semana de Mayo).

The May Revolution was a direct reaction to developments in Spain during the previous two years. In 1808 the Spanish king, Ferdinand VII had been convinced to abdicate by Napoleon in his favor, who granted the throne to his brother, Joseph Bonaparte. A Supreme Central Junta had led a resistance to Joseph's government and the French occupation of Spain, but eventually suffered a series of reversals resulting in the loss of the northern half of the country. On February 1, 1810, French troops took Seville and gained control of most of Andalusia. The Supreme Junta retreated to Cadiz and dissolved itself in favor of a Regency Council of Spain and the Indies. News of this arrived in Buenos Aires in May 18 on British ships bringing newspapers from Spain and the rest of Europe.

Initially, Viceroy Cisneros tried to conceal the news in order to maintain the political statu quo, but he was unsuccessful. With the news of the turn of events in Spain, a group of Criollo lawyers and military officials organized an open cabildo (an extraordinary meeting of notables of the city) on May 22 to decide the future of the Viceroyalty. At this meeting it was decided to deny recognition to the Council of Regency in Spain, to end Cisneros' mandate as Viceroy since the government that appointed him no longer existed, and to establish a junta to govern in his place. In order to maintain a sense of continuity, Cisneros himself was initially appointed as the President of the Junta. However, this caused a great deal of popular unrest since it ran counter to the reasons for which his mandate was ended, so Cisneros resigned under pressure on May 25. Subsequently, the newly formed Primera Junta invited the other cities of the Viceroyalty to send delegates to join the Buenos Aires Junta, but this resulted in the outbreak of war between the regions that accepted the outcome of the events at Buenos Aires, and those that did not.

The May Revolution is considered the starting point of the Argentine War of Independence, although no formal declaration of independence was issued at the time, and the Primera Junta continued to govern in the name of the deposed king Ferdinand VII. As similar events occurred in many other cities of the Spanish South America when news of the dissolution of the Spanish Supreme Junta arrived, the May Revolution is also considered as one of the starting points for the Spanish American wars of independence. Historians today debate whether the revolutionaries were truly loyal to the Spanish crown, or whether the declaration of fidelity to the king was a necessary ruse to conceal the true objective of achieving independence for a population that was not ready yet to accept such a radical change. A formal Declaration of Independence was only issued at the Congress of Tucumán on July 9, 1816.

Contents |

Causes

International causes

The United States had emancipated themselves from the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1776, which provided a tangible example that led Criollos to believe that revolution and independence from Spain could be realistic aims.[1] In the time between 1775 and 1783 the Thirteen Colonies started the American Revolution, first rejecting the governance of the Parliament of Great Britain, and later the British monarchy itself, and waged the American Revolutionary War against their former rulers. The changes were not just political, but also intellectual and social, combining both a strong government with personal liberties. They had also chosen a republican form of government, instead of keeping a monarchic one. Even more, the fact that Spain aided the colonies in their struggle against Britain weakened the argument that ending allegiance to the mother country could be considered a crime.[2]

The ideals of the French Revolution of 1789 were spreading as well. During the Revolution, centuries of monarchy were ended with the overthrow and execution of the King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, and the removal of the privileges of the nobility. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was highly popular among the young Criollos. The French Revolution also boosted liberal ideals in political and economic fields. Some of the most notable politically liberal authors, who opposed monarchies and absolutism, were Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu, Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d'Alembert. Liberal ideas also reached the church, and the concept of the divine right of kings started to be questioned.[3] The end of the consensus about the divine right being legitimate gave room for republics in France and the United States to replace monarchies. It also gave rise to constitutional monarchies, such as in Great Britain.[4]

However, the spread of such ideals was mainly forbidden in the Spanish territories, as well as the traffic of related books or their unauthorized possession. Such blockades started when Spain declared war on France after the execution of Louis XVI, but was kept as well after the peace treaty of 1796. Nevertheless, the events of 1789 and the statements of the French Revolution spread around Spain despite the efforts to keep them at bay. Many enlightened Criollos came into contact with those authors and their works during university studies,[5] such as Manuel Belgrano in Spain[6] or Mariano Moreno[7] and Juan José Castelli[8] at the University of Chuquisaca, the only one of its kind at the Spanish America by the time. Books from the US also found their way into the Spanish colonies through Caracas, due to the closeness of Venezuela to the United States and West Indies.[9]

The Industrial Revolution started in Britain, with manual labour and horse-drawn vehicles being replaced by machine-based manufacturing and transportation aided by railways and steam power. This led to dramatic increases in the productive capabilities of Britain,[10] and the need for new markets to sell their products. The Napoleonic Wars, where Britain was at war with France, made this a difficult task, after Napoleon countered the British naval blockade with the Continental System, not allowing Britain to trade with any other European country. Thus, Britain needed to be able to trade with the Spanish colonies,[11] but could not do so because they were restricted to trade only with their own metropoli.[12] To achieve this end, they initially tried to conquer key cities in Spanish America. Failing at it, they chose to promote the Spanish American aspirations of emancipation from Spain.[12] The Industrial Revolution also gave room to authors who proposed a liberal economy, like Adam Smith or François Quesnay.

Portugal broke the blockade imposed on British trade and, as a result, was invaded by France.[13] However, the Royal Family and the bulk of the kingdom's administration fled to colonial Brazil, in a move to preserve Portuguese sovereignty. Under the pretext of reinforcing the Franco-Spanish army occupying Portugal, French Imperial troops began marching into Spain, shortly before the Spanish King Charles IV abdicated in favor of his son, Ferdinand VII, due to the mutiny of Aranjuez.[14] Feeling that he had been forced to abdicate, Charles IV requested that Napoleon restore him to the throne. Napoleon helped remove Ferdinand VII from power, but did not return the crown to the former king; instead, he crowned his own brother Joseph Bonaparte as the new Spanish King.[14] This whole process is known as the Abdications of Bayonne. However, Joseph's crowning found severe resistance in Spain, and the Junta of Seville took power in the name of the absent King. Until then, Spain had been a staunch ally of France against Britain but, from then on, the Spanish resistance changed sides and allied with Britain against France. The Junta of Seville was eventually defeated, and was replaced by a Regency Council based in Cádiz.

National causes

Spain had adopted in the Americas the policy of banning its colonies from trading with other nations or foreign colonies, imposing itself as the only buyer and vendor in their international trade. This situation damaged the viceroyalty, as Spain's economy was not powerful enough to accommodate the supply of goods coming from the colonies,[15] leading to economic shortages and recession. Buenos Aires was even more damaged, as Spain did not send enough ships to the city, whenereas Mexico or Lima had more lucrative relations with their metropoli. This led Buenos Aires to develop a system of smuggling to obtain, by illegal means, the products that could not be gotten legitimately. This smuggling was allowed by most local authorities as a lesser evil, and it eventually equalled in volume the legal commerce with Spain.[16] This whole situation created two antagonistic groups: exporters who wanted free trade to be able to sell their products, and retailers who benefited from the prices of the smuggled imports, which they would have had to sell at lower prices if free trade was allowed.

Politically, the most authoritative positions in the Viceroyalty were filled by people directly named by the Spanish Monarchy, most of them being Spaniards from Europe, whithout any strong interest in American problems or issues. This resulted in a growing rivalry between the Criollos, the people born in America, and the Peninsulares, the people arrived from Europe (the term "Criollo" is usually translated to English as "Creole", despite them being completely unrelated to most other Creole peoples). Despite the fact that all of them were considered Spanish, most Criollos thought that Peninsulares had undue weight in politics and desired more rights and political access. This was a sentiment shared by the lower clergy respective to the higher echelons of the religious hierarchy.[17] However, this whole conflicting process devoloped at a much slower pace than the experience in the British colonies in North America, in part because the entire educational system was controlled by the clergy, influencing the population into the same conservative customs and ideas as those of metropolitan Spain.[18]

Buenos Aires and Montevideo had successfully resisted two British invasions. The first one was in 1806, when a British army led by William Carr Beresford briefly took control of Buenos Aires, until being defeated by an army from Montevideo, led by Santiago de Liniers. The following year a bigger army took Montevideo, but failed to take Buenos Aires, and it was forced to surrender and to leave both cities. There was no Spanish aid from Europe during both two invasions, and the preparations for the second one included the formation of Criollo militias, despite the regulations that prohibited this. The biggest Criollo army was the Patricios Regiment led by Cornelio Saavedra.[19] This events gave Criollos the military power and political influence that they did not have had before. Moreover, as the victory was achieved without any help from Spain, it also boosted the Criollo confidence on their independent capabilities, showing them that the Spanish aid was not needed.[20]

By 1808, as Portugal was invaded by Napoleon, the Portuguese Royal Family left Europe and settled in colonial Brazil. The Prince arrived with his wife, Charlotte Joaquina, who was the daughter of Charles IV of Spain and sister to Ferdinand VII. When the news of the imprisonment of the latter arrived in South America, Charlotte tried to take over the Spanish Viceroyalties as a regent. This political project, known as Carlotism, was intended to prevent a Napoleonic French invasion to the Americas. Some Criollos, including Castelli, Beruti, Vieytes and Belgrano supported this project, considering it a good chance to get a local government instead of a European one, or as a step towards a later declaration of independence.[21] Other Criollos, including Moreno, Paso and Saavedra were against this project, as were most peninsular Spaniards and Viceroy Liniers. They all suspected that the whole project concealed the Portuguese expansionist ambitions over the region.[22] Charlotte finally rejected the plan, as her supporters intended her to head a constitutional monarchy, while she wanted to govern an absolute monarchy. Britain, which had a strong stance in the Portuguese Empire, also opposed the project: they did not want to let Spain to be split into many kingdoms, as they did not consider Charlotte to be able to prevent separatism in the Spanish colonies.[23]

Prelude

Liniers government

After the successful liberation of Buenos Aires from the British troops at the aforementioned British Invasions, the population refused to let Rafael de Sobremonte remain as the Viceroy. There was dissatisfaction about him leaving the city and moving to Córdoba with the public treasury, while Buenos Aires was under attack. Although his action was in line with a law enacted by former Viceroy Pedro de Cevallos, which required the treasury to be kept safe in case of a foreign attack, he was seen as a coward by the population because of it.[24] The Real Audiencia of Buenos Aires did not let him return to Buenos Aires or resume governing, and elected instead Santiago de Liniers, acclaimed as a popular hero, as an interim Viceroy. This appointment was later confirmed by the King Charles IV of Spain.[25] This was an unprecedented action: it was the first time that a Spanish viceroy was deposed by local government institutions, and not by the Spanish king himself. Under Liniers' rule, all the population of Buenos Aires was armed, including criollos and slaves, so a second British invasion attempt was successfully resisted.

The government of Liniers was popular among Criollos, but found resistance from peninsular Spaniards, such as the merchant Martín de Álzaga or the governor of Montevideo, Francisco Javier de Elío.[26] De Elío created a Junta in Montevideo, which would scrutinise all the orders coming from Buenos Aires and reserved the right to ignore them, without openly denying the authority of the Viceroy or declaring themselves independent.

Martín de Álzaga set off a mutiny in order to remove Liniers. On January 1, 1809, an open cabildo demanded the resignation of the Viceroy Liniers and appointed a Junta on behalf of Ferdinand VII, chaired by Álzaga; the Spanish militia and a group of people summoned by the bell of the council gathered to support the rebellion. A small number of Criollos (notably Mariano Moreno) supported the mutiny as a means to gain independence, but most of them did not.[27] The lawyer Juan José Castelli even started a legal case against Álzaga accusing him of independentism. The seeming contradiction is explained in that the goals of Álzaga were not those of the Criollos: he wanted to remove the Viceroy to avoid being constrained by his political authority, but he intended to keep the social differences between Criollos and European Spaniards unchanged.[28]

The riot was quickly routed as Criollo militias led by Cornelio Saavedra surrounded the plaza, causing the insurgents to disperse. The leaders were exiled, and the rebel units were dissolved. As a result of the failed mutiny, Buenos Aires military power was de facto transferred to the locals who had sustained Liniers: all military units still active after the riot were Criollo, and there were no militias left that would answer to the peninsular Spaniards. The rivalry between Criollos and peninsular Spaniards thus deepened. The perpetrators of the plot, with the exception of Moreno, exiled to El Carmen, from where they were rescued by Elío and taken to Montevideo.[29]

Cisneros government

In Spain, the Junta of Seville decided to end the fighting in the Río de la Plata, providing a replacement for Liniers in Don Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, who arrived in Montevideo on June 1809. Manuel Belgrano proposed Liniers to resist his removal and to reject the appointment of Cisneros, on the grounds that Liniers had been confirmed as Viceroy by the authority of a Spanish king, while Cisneros would lack such legitimacy.[30] Nevertheless, Liniers accepted to give up his government to Cisneros without resistance. Javier de Elío accepted as well the authority of the new Viceroy and dissolved the Junta of Montevideo. Cisneros rearmed the Spanish militias that were disbanded after the coup against Liniers, and pardoned the responsibles.[31] Álzaga was not freed, but his sentence was changed to house arrest.

Cisneros tried to be welcomed by the British and the Hacendados (owners of Haciendas) by removing the laws that forbid free trade, but retailers forced Cisneros to restore such laws. Mariano Moreno, a criollo lawyer, wrote a document to request Cisneros the reopening of free trade, entitled "The Representation of the Hacendados". It is considered the most comprehensive economic report of the time.[32] Cisneros finally decided to grant an extension of free trade, which would end on May 19, 1810.[33]

Concern about the events in the Peninsula and the legitimacy of the local authorities was also expressed in Upper Peru. On May 25, 1809, a revolution in Chuquisaca deposed the governor and president of the Royal Audiencia of Charcas, Ramón García de León y Pizarro, and accused him of supporting a Portuguese protectorate under the authority of Charlotte Joaquina. Military command fell to Colonel Juan Antonio Alvarez de Arenales who, due to uncertainty as to who should be in charge of the civilian affairs, also exercised some civil powers.[34] On July 16, in the city of La Paz, a second revolutionary movement led by Colonel Pedro Domingo Murillo forced the governor to resign and replaced him with a Junta, the "Junta Tuitiva de los Derechos del Pueblo" ("Junta, keeper of the rights of the people"), headed by Murillo.[34]

A quick reaction from the Spanish officials soon defeated these rebellions. An army with 1,000 men sent from Buenos Aires found no resistance at Chuquisaca, took control of the city, and deposed the Junta.[34] Similarly, Murillo's 800 men were completely outnumbered by the more than 5,000 men sent from Lima.[34] He was later beheaded along with other leaders and their heads exhibited to the people as deterrent.[34] The measures taken against those revolutions reinforced the feeling of inequity among Criollos, more so because they greatly contrasted against the pardon that Martín de Álzaga and others received after serving just a few time in jail. This further deepened the resentment of the locals against the peninsular Spaniards.[35] Among others, Juan José Castelli was present at the proceedings of the University of Saint Francis Xavier where the Syllogism of Chuquisaca was developed. This would greatly influence his position during the May week.[36]

On November 25, 1809 Cisneros created the Political Surveillance Court with the aim of pursuing the supporters of "French ideologies", and those who encouraged the creation of political regimes that opposed the dependence on Spain.[37] However, he rejected a proposal of the economist José María Romero to banish a number of people which were considered dangerous to the Spanish regime: Saavedra, Paso, Chiclana, Vieytes, Balcarce, Castelli, Larrea, Guido, Viamonte, Moreno, Sáenz and Belgrano, among many others.[38] All these measures, and a proclamation issued by the Viceroy to prevent the spreading of news that might be considered subversive, made the Criollos think that a formal pretext would be enough to take actions that would lead to the outbreak of a revolution. On April 1810, Cornelio Saavedra expressed his famous quote to his friends: It's not time yet, let the figs ripen and then we'll eat them.[39]

May week

Academics usually call "May Week" the period of time beginning with the confirmation of the fall of the Junta of Seville, and ending with the dismissal of Cisneros and the establishment of the Primera Junta.[40]

On May 14, the British war schooner HMS Mistletoe arrived at Buenos Ares from Gibraltar, carrying newspapers dated last January that announced the dissolution of the Junta of Seville. The city of Seville was taken by the French, who were already in control of the most part of the Iberian Peninsula. The Junta, one of the last bastions of the Spanish crown had fallen to the Napoleonic Empire, which had previously removed the King Ferdinand VII through the abdications of Bayonne. The newspapers also stated that some of the Spanish Junta members had taken refuge on the island of León in Cadiz. Such news were confirmed in Buenos Aires on the 17th, with the arrival in Montevideo of the British frigate HMS John Paris; the news provided by it added as well that members of the Junta of Seville had been refused. The Regency Council of Cádiz was not seen as a succesor of the Spanish resistance, but as an attempt to restore absolutism in Spain, whenereas the Junta of Seville was seen as akin to the new ideas; and South American patriots feared both a complete French victory in the peninsula and an absolutist restauration.[41] Cisneros tried to hide the news by establishing rigorous monitoring around the British warships and seizing every newspaper that landed from the boats, but one of them came into the hands of Manuel Belgrano and his cousin Juan José Castelli.[42] They were responsible for spreading the news, which challenged the legitimacy of the Viceroy, appointed by the fallen Junta.[42]

Cornelio Saavedra, head of the regiment of Patricians, who in the past had advised against taking rushed actions against the Viceroy, was also made aware of the news. Saavedra considered, from a strategic standpoint, that the ideal time to proceed with the revolutionary plans would be the time when Napoleon's forces gained a decisive advantage in their war against Spain. Upon hearing the news of the fall of the Junta of Seville, Saavedra decided that the perfect time to take action against Cisneros had arrived.[43] Martín Rodríguez proposed to overthrow the viceroy by force, but Castelli and Saavedra rejected this idea and preferred the celebration of an open cabildo.[44]

Friday, May 18 and Saturday, May 19

Viceroy Cisneros attempted to conceal the news from the people; however, the rumor had already spread throughout Buenos Aires. Most of the population was concerned about the news, there was high activity at the barracks and the Plaza, and most shops were closed.[45] The "Coffeehouse of Catalans" and the "Fonda of Nations", usual meeting places of criollos, became a place for political discussions and radical proclamations; Francisco José Planes shouted that Cisneros should be hanged in the Plaza in response to the execution of the leaders of the ill-fated La Paz revolution.[46] The sympathizers of the absolutist government were harassed in those places, but the fights were of little importance because nobody was allowed to take muskets or swords out of the barracks.[47]

The Viceroy decided to give his own version of the events through a proclamation, while trying to calm down the Criollos. He asked for allegiance to King Ferdinand VII, but popular unrest continued to intensify. Despite being aware of the news,[48] he only said that the situation in the Iberian Peninsula was delicate, but did not confirm the fall of the Junta. His proposal was to make a government body that would rule in behalf of Ferdinand VII, toguether with Abascal, Sanz and Nieto.[49]

{{cquote|In Spanish America the throne of the Catholic Monarchs will endure, in the case it succumbs on the peninsula. (...) The superior government will not make any determination that is not previously agreed upon in union with all representatives of the capital city, to which subsequently will join those of the dependent provinces, until, in agreement with the other Viceroyalties, a representation of the sovereignty of Ferdinand VII is established.[50]

Not fooled by the Viceroy's communiqué, some Criollos met at the houses of Nicolás Rodríguez Peña and Hipólito Vieytes. During these secret sessions they decided to name a representative commission, composed by Juan José Castelli and Martín Rodríguez, to ask Cisneros for an open cabildo. They intended to decide there the future of the Viceroyalty.

During the night of May 19 there were further discussions at Rodríguez Peña's house. It was requested to Viamonte to call Saavedra, who joined the meeting. There was a number of both military leaders, such as Rodríguez, Ocampo, Balcarce, Díaz Vélez, and civilian ones such as Castelli, Vieytes, Alberti and Paso. It was decided that Belgrano and Saavedra would meet with senior alcalde Juan José de Lezica, and Castelli with the procurator Julián de Leyva, asking them for the support of the cabildo. They wanted to ask the Viceroy to allow an open cabildo, saying that if it was not freely granted, the people and the Criollo troops would march to the Plaza, force the viceroy to resign by any means necesary, and replace him with a patriot government.[51] Saavedra also commented Lezica that he was suspected of being a potential traitor by his peers because of his constant request of cautious and measured steps. This comment was formulated to build more pressure over Lezica, by placing him in he disyuntive of speeding up the legal systems to allow the people express themselves, or the risk of an important rebellion.[52] Lezica requested to the others to be patient and give him time to persuade the viceroy, leaving such a massive demonstration as a last resource. He argued that if the viceroy was deposed that way, it would constitute a rebellion,[53] and turn the revolutionaries into outlaws before the other cities. Manuel Belgrano gave the following Monday as the deadline to confirm the Open Cabildo before taking direct action.[54] Later on, during the Revolution, Leyva would act as a mediator for both sides, being both a confidant for Cisneros and a trusted negotiator for the moderate revolutionaries.[55]

Sunday, May 20

Lezica sent Cisneros the request he had received, and then the Viceroy consulted Leyva, who favored the call for an open cabildo. Before deciding, the Viceroy summoned military commanders to come forward at seven o'clock in the evening at the fort. There were rumors that it could be a trap to capture the commanders and take control of the barracks. To avoid facing such risk, they took command of the granediers that guarded the Forst and secured the keys of all entrances to it, while meeting with the viceroy.[56] Cisneros demanded a response to his request for military support, and Colonel Cornelio Saavedra, head of the Patricios Regiment, responded on behalf of all the locally born regiments saying:

{{cquote|Sir, January 1, 1809, and May 1810, in which we find ourselves, are very different times. Then there was Spain, even if already invaded by Napoleon. In this, all of it, all of its provinces and plazas but Cadiz and the Isle of León, are subjugated by that conqueror, as the newspapers that just arrived, and V.E. in his proclamation of yesterday, say. And what, sir? Cadiz and the Isle of León are the whole Spain? This immense territory, its millions of inhabitants, have to acknowledge sovereignty in the merchants of Cadiz and the fishermen of the Isle of León? Do the rights of the Crown of Castile who the Americas entered into, have fallen into Cadiz and the Isle of Leon, which are a just a part of one of the provinces of Andalucia? No sir, we do not want to follow the fortunes of Spain, nor be dominated by the French. We have decided to resume our duties and keep us by ourselves. Those who had given V.E. the authority to rule us no longer exist; consequently, you don't have it anymore. Do not count on the strength of my command to hold it.[57]

There was a new meeting at Rodríguez Peña's home at midnight, where the military leaders explained the events that were taking place. Castelli and Martín Rodríguez were then sent to the Fort for a new interview with Cisneros. Terrada, commander of the Infantry Grenadiers, join them for this interview because the barracks of the military bodies under his command were located under Cisneros' window, and his presence would prevent him from requesting military aid to take them prisoners.[58] The guardians let them pass unannounced, and they found Cisneros playing cards with brigadier Quintana, prosecutor Caspe and aide Coicolea. Castelli and Rodríguez demanded once again an open cabildo, and Cisneros reacted in anger, considering their request an outrage. But Rodríguez interrupted him and forced him to give a definitive answer.[59] After a short private discussion with Caspe, Cisneros reluctantly gave his consent to the call for an open cabildo.[59] It would be opened on May 22.

On the same night there was a theatre production on the theme of tyranny, called "Rome Saved", which was attended by many of the revolutionaries. The police chief tried to convince the actor not to appear on stage and to excuse himself for being ill, so the play could be replaced with "Misanthropy and repentance", by the German poet August von Kotzebue. Rumors of police censorship spread quickly, so the actor Morante decided to make himself present and performed the play on tyranny as planned, his role being Cicero. In the fourth act, Morante made a patriotic roman speech, talking about Rome being menaced by the gallus and the need to have a strong leadership to resist the danger.[60] This scene flared the revolutionary spirits, which led to frenzied applause to the work. Juan José Paso stood up and shouted ¡Viva Buenos Aires libre! ("Long live free Buenos Aires!"), which produced a small fight with other people present.[60]

After the play, the revolutionaries were called once again to Peña's house. They learned the result of the last meeting, and were unsure about Cisneros truly intended to keep his word. As a result, they decided to organize a demonstration for the following day, in order to ensure that the open cabildo was celebrated as decided.[60]

Monday, May 21

At 3pm, the Cabildo began its work routine, but was interrupted by 600 armed men, grouped under the name "Infernal legion" (Spanish: Legión Infernal), which occupied the Plaza de la Victoria, nowadays Plaza de Mayo, and loudly demanded the convention of an Open Cabildo and the resignation of Viceroy Cisneros. They carried a portrait of Ferdinand VII and the lapel of their jackets bore a white ribbon symbolizing the Criollo-Spanish unity. The rioters were led by Domingo French, the mail carrier of the city, and Antonio Beruti, employee of the treasury. The demonstration was so strong that some rumors circulated saying that Cisneros had been killed in it and that Saavedra would take the government.[61] Saavedra was at the barracks at that moment, concerned about the demonstration. He thought that violence should be stopped and that radical measures such as the death of Cisneros should be prevented, but he also thought that if the demonstrations were repressed the only result would be that the troops would mutiny and refuse to carry out such orders.[62] In the Plaza, the people distrusted Cisneros and did not believe he was going to keep his word to allow the making of the open cabildo the next day. Leiva left the Cabildo and Belgrano, representing the crowd, requested a definitive answer. Leiva explained that everything would go on as planned, but the Cabildo needed time to arrange the preparations. Leiva requested Belgrano to help the Cabildo with such work, as his intervention would be seen by the crowd as a guarantee that their demands would not be ignored. The crowd left the main hall, but stayed in the Plaza. Belgrano protested the list of guests, made of the wealthiest members of the city, and thought that if the poor people were left outside there would be further social unrest. The members of the Cabldo tried to convince him to give his support, but he left the place instead.

Belgrano's departure enraged the crowd, as he did not explain what had happened, and the people feared a betrayal from the Cabildo. The demands for the Open Cabildo were replaced by demands for Cisneros' immediate resignation. The people finally settled down and dispersed through the intervention of Cornelio Saavedra, head of the Regiment of Patricians, who said that the claims of the Infernal Legion had their military support.[63]

On May 21 invitations were distributed among 450 leading citizens and officials in the capital. The guest list was compiled by the Cabildo, trying to guarantee the result by selecting people that would be likely to support the Viceroy. For this, they prepared a list a guests taking into account the most prominent residents of the city. However, the revolutionaries countered such move by making a similar one on their own: Agustín Donado (French and Beruti colleague), in charge of printing the invitations, printed nearly 600 of them, instead of just the 450 requested, and distributed the surplus among the Criollos.[64] By the night, Castelli, Rodríguez, French and Beruti visited all the barracks to harangue the troops and prepare them for the following day.[65]

Tuesday, May 22

According to the official acts, out of 450 invited guests to the open cabildo only about 251 attended.[66] French and Beruti, commanding 600 men armed with knives, shotguns and rifles, controlled access to the square, with the aim of ensuring that the open cabildo had a majority of Criollos. All the noteworthy religious and civilian people were present, as well as militia commanders and many prominent neighbours (the only notable absence was that of Martín de Álzaga, still under house arrest). The troops were garrisoned and on alert, ready to take action in case of commotion.[67] The trader José Ignacio Rezábal attended, but explained his doubts to do so in a mail to the priest Julián S. de Agüero, telling as well that his doubts were shared by other people close to him. He feared that both political flows would take revenge against the supporters of the other if they prevailed, with the Mutiny of Álzaga as a close antecedent.[68] He also considered that the Open Cabildo would lack legitimacy if the Criollos were allowed to take part in it in great numbers, because of the aformentioned manipulation of the guest list.[68]

The meeting lasted from morning to midnight, with various times, including the reading of the proclamation of the Cabildo, the debate, and the vote, individual and public, written by each attendee and past the minutes of the meeting. The debate in the council had as its main theme the government's legitimacy and the authority of the Viceroy. The principle of retroversion of the sovereignty to the people stated that, missing the legitimate monarch, the power returned to the people; and they were entitled to form a new government. This principle was commonplace in Spanish scholasticism and rationalist philosophy, but had no precedents of being applied in case law.[69]

There were two main positions at the assembly, one from those who argued that the situation should remain unchanged, supporting Cisneros in his office of Viceroy, and the one from those who believed that they should establish a Junta to replace him, as the ones established in Spain. There was also a third position, between both.[70] The promoters of the change did not recognize the authority of the Regency Council, arguing that the colonies in America were not consulted to its formation. The debate also covered, tangentially, the rivalry between Criollos and the peninsular Spanish, as proponents of keeping the Viceroy considered that the will of the Spaniards should prevail over that of the Criollos.

One of the speakers at the first position was the bishop of Buenos Aires, Benito Lue y Riega, leader of the local church. Lue y Riega argued that:

| “ | Not only there is no reason to make news with the Viceroy, but even if there was no land of Spain that was not subdued, the Spaniards in America ought to take it and resume command over it. America should only come to the hands of the sons of the country when there was no longer a Spanish there. Although it would be a single member of the Central Junta of Seville up on our shores, we should receive him as the Sovereign.[71] | ” |

Juan José Castelli was the main orator for the revolutionaries. He based his speech on two main ideas: the expiration of the legitimate government, stating the Junta of Seville was dissolved and had no rights to designate a Regency, and the mentioned principle of retroversion of sovereignty.[72] He spoke after Riega, arguing that the American people should assume the control of their destiny until the impediment for Ferdinand VII to return to the throne would cease.

{{cquote|Nobody could repute the whole nation as a criminal, nor the individuals that have aired their political views. If the right of conquest belongs, by right, to the conqueror country, it would be fair that the Spain started to give reason to the priest by giving up the resistance made against the French and submitting to them, by the same principles for which it is expected that the Americans submit themselves to the peoples of Pontevedra. The reason and the rule must be equal for everybody. There are no conquerors or conquered here, there aren't here but Spanish people. The Spaniards of Spain have lost their land. The Spanish Americans try to save theirs. Let the ones from Spain deal with themselves as they can and do not worry, we Americans know what we want and where we go. Thus, I suggest we vote: that we enact an authority other than the Viceroy, that will be a subject to the metropoli if it gets saved from the French, and that will be independent if Spain is finally subjugated.[73]

Pascual Ruiz Huidobro stated that since the authority that had appointed Cisneros had expired, he should be left apart from any function of government, and that in its role as representative of the people, the council should assume, and exercise, authority. His vote was supported by Melchor Fernández, Juan León Ferragut, Joaquín Grigera, among others.[74]

Attorney Manuel Genaro Villota, representative of the conservative Spanish, said that the city of Buenos Aires had no right to make unilateral decisions about the legitimacy of the Viceroy or the Regency Council without the participation of other cities of the Viceroyalty in the debate. He argued that such an action would break the unity of the country, establishing as many sovereignties as cities. The purpose of such a point of view was to keep Cisneros in power by delaying any possible action.[75] Juan José Paso accepted him being right at the first point, but argued that the conflicted situation in Europe and the possibility that Napoleon's forces may continue conquering the American colonies were demanding an urgent resolution.[76] He then exposed the "argument of the oldest sister", reasoning that Buenos Aires had to take initiative to make the changes deemed necessary and appropriate, upon the express condition that the other cities would be invited to comment on it as soon as it was possible.[77] The rhetorical figure of the "oldest sister", comparable to business management, is a name that makes an analogy between the relationship of Buenos Aires and other cities of the viceroyalty with a filial relationship.[77]

The priest Juan Nepomuceno Solá then proposed that the provisional command should be given to the Cabildo, until the completion of a governing Junta made up of representatives from all populations of the Viceroyalty. His motion was supported by Manuel Alberti, Azcuénaga, Escalada, Argerich or Aguirre, among others.[74]

Cornelio Saavedra then suggested that the control should be delegated instead to the council until the formation of a governing junta in the manner and in the form that the council would deem as appropriate. He pointed out the phrase "(...) and there is no doubt that it is the people that makes the authority or command."[66] At the time of the vote, Castelli's position coupled with that of Saavedra.[78]

Manuel Belgrano was standing near a window, so that in case of a problematic development of the open cabildo procedures he would give a signal by waiving a white cloth. In that case, the people gathered in the Plaza would have forced their way into the Cabildo. However, there were no problems at all, and this emeregency plan was not implemented.[79] The historian Vicente Fidel López, son of Vicente López y Planes, revealed that his father, present in the event, saw that Mariano Moreno was worried near the end, despite of the majority achieved. Moreno told Planes that the Cabildo was about to betray them.

Wednesday, May 23

The debate took all day, and the vote counting took place very late in the night. After the presentations, a vote was taken by the continuity of the Viceroy, alone or associated, or dismissal. The ideas explained were divided into a small number of proposals, designated after their main supporters, and the people would then vote for one of those proposals. The voting lasted for a long time, and decided to dismiss the Viceroy by a large majority: 155 votes to 69. The votes against Cisneros were distributed as follows:[78]

- Plan under which the authority vested in the Cabildo: 4 votes

- Plan Juan Nepomuceno de Sola: 18 votes

- Plan Pedro Andres Garcia, Juan José Paso and Luis Jose Chorroarín: 20 votes.

- Plan Ruiz Huidobro: 25 votes

- Plan Saavedra and Castelli: 87 votes

At dawn on May 23 a document was released, stating that the Viceroy should end his mandate. The maximum authority would be temporarily transferred to the Cabildo, until the designation of a governing Junta.[80] Notices were placed at various points throughout the city announcing the imminent creation of a Junta and the summoning of representatives from the provinces. The notices also called the public to refrain from attempting actions contrary to public policy.[81]

Thursday, May 24

On the 24th, the Cabildo, following a proposal by the liquidator Leyva, interpreted the results of the open cabildo and conformed the new Junta, which was to be active until the arrival of the representatives from the rest of the Viceroyalty. Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros was named the president of the Junta, and commander of the armed forces. He was chosen along with other four members: the Criollos Cornelio Saavedra and Juan José Castelli, and the Spaniards Juan Nepomuceno Solá and José Santos Inchaurregui.[81] There are many interpretations of the motives for this action. Historian Diego Abad de Santillán states that the formula responded to Bishop Benito Lue y Riega proposal of keeping the Viceroy in power along with partners or attachments, even though the same proposal had been recently defeated at the open cabildo votation. Abad de Santillán argues that this formula made the lobbyists believe that they could contain the threat of a revolution that was taking place in society.[81] Félix Luna, on the other hand, considers that it was an effort to avoid further conflicts, by choosing a middle ground solution, conceding something to all the parties involved, as Cisneros would remain in office, but sharing the power with the Criollos.[82]

It was included a constitutional corpus of 13 articles, written by Leyva, to regulate the actions of the Junta. Among the principles included there, it was ruled that the Junta could not exercise the judicial power, which would be exercised by the Court, that Cisneros could not act without the backing of the other members of the Junta, that the council could depose the Junta members who neglected their duty, that it must approve the proposals for any new taxes, that it which would sanction a general amnesty on the opinions aired at the open council of May 22, and that the councils would request them to send deputies inside. The armed forces's commanders gave their agreement to this, including Saavedra and Pedro Andrés García. The Junta made the oath of office during the afternoon.[83]

The news took the revolutionaries by surprise. They were unsure of what to do next, and feared that they would be punished like the revolutionaries of Chuquisaca and La Paz. Moreno abjured relations with the others and enclosed himself in his home.[84] There was meeting at Rodríguez Peña's house. It was thought that the Cabildo wouldn't go on with a proposal like that without the blessing of Saavedra, and that Castelli should resign from the Junta. Tagle rejected the proposal: he thought that Saavedra may had accepted out of weakness or naivety, and that Castelli should stay near to counter the other's influence over him.[85] Meanwhile, the Plaza was invaded by a mob led by French and Beruti. Cisneros staying in power, albeit in a different office than Viceroy, was seen as an insult to the will of the open cabildo. Colonel Martín Rodriguez explained that if their soldiers were ordered to support Cisneros, they would have to open fire against the population and that even most of the soldiers would revolt, as they shared the desire to remove the Viceroy from power.[86]

At night, Castelli and Saavedra talked with Cisneros to inform about their resignation to the newly formed Junta. They explained that the population was on the verge of a violent revolution to remove Cisneros by force if he didn't resign as well. They also pointed that they did not had the power to stop that: neither Castelli to stop his friends, nor Saavedra to prevent the Regiment of Patricians from mutiny.[87] Cisneros wanted to wait for the following day, but they said that there wasn't time for further delays. He finally accepted to resign. He wrote his resignation and sent it to the Cabildo, which would consider it on the following day. Chiclana felt encouraged when Saavedra decided to resign, and started to work requesting signatures for a manifest of the will of the people. Moreno refused any further involvement, but Castelli and Peña trusted that he would eventually join them if the events unfolded as tey had planned.[88]

Friday, May 25

On the morning of May 25, despite the bad weather, a crowd gathered at Plaza de la Victoria, as it did the militia led by Domingo French and Antonio Beruti. They all demanded the revoking of the Junta elected the previous day, the final resignment of Viceroy Cisneros and the composition of a new Junta without him. The historian Bartolomé Mitre stated that French and Beruti distributed blue and white ribbons among the guests, but later historians doubt it, but considering that it was possible that the distinctives were distributed among the revolutionaries for identification.[89] Despite Cisneros having resigned the night before, it was rumored that the Cabildo may reject his resignation.[90] Due to the delays in the issue of an official resolution, people began to stir, claiming that "The people want to know what it is all about!".

The Cabildo met at nine in the morning and rejected Cisneros' resignation. They considered that the crowd had no legitimacy to influence over something that the Cabildo had already decided and performed. They considered that, as the Junta was in command, the popular agitation should be suppressed by force, and made the members responsable for any changes.[91] To enforce those orders, they summoned the chief commanders, but they did not obey. Many of them, including Saavedra, did not show, and those that did show stated that they could not support the government order, and that even the commanders themselves would be disobeyed if they ordered the troops to repress the demonstrators.

The crowd's agitation led to the chapter house being overrun. Leiva and Lezica requested that someone that may act as spokeman of the people joined them inside the hall and explain the people's desires. Beruti, Chiclana, French and Grela were allowed to pass. Leiva attempted to discourage Pancho Planes from joining them, but he sneaked in the hall as well.[92] The Cabildo argued that Buenos Aires had no right to break the political system of the viceroyalty without discussing it with the other provinces, and French and Chiclana replied that the calling for a Congress was already considered. The Cabildo decided then to call for the commanders to deliberate with them. As in previous similar requests to other commanders, Romero explained that their soldiers would mutiny if forced to fight against the rioters in behalf of Cisneros. The Cabildo still refused to give up, until the noise of the demonstration was hear in the hall. They feared that the demonstrators may overrun the complete building and reach them. Martín Rodríguez pointed that the only way to calm the demonstrators would be if the Cabildo accepted at last Cisneros' resignation. Leiva agreed, convinced the other members, and the people returned to the Plaza. Rodríguez headed to the Azcuenaga house to meet the other revolutionaries, and they decided that they only needed one final step. The demonstration overruned the Cabildo again, this time reaching the hall of deliberations. Beruti spoke in behalf of the people, and pointed that the new Junta should be elected by the people and not by the Cabildo. He threatened that, besides the nearly 400 people gathered in the demonstration, the barracks were still full people loyal to them, who would take control by force if needed. The Cabildo replied by requesting their demands in a written, signed form. After a long interval, a document containing 411 signatures was delivered to the Cabildo. This paper proposed a new composition for the governing Junta, and a 500 men expedition to assist the provinces.

The document (still conserved) had the signatures of most army commanders, many well-known neighbours, and many illegible ones. French and Beruti signed the document stating "for me and for six hundred more".[93] However, there is no unanimous view among historians about the authorship of the content of that document. Saavedra in his memories, as well as liberal historians like Vicente Fidel López, claim that it was exclusively a product of the popular initiative, despite being an imprecise suggestion.[94] For others, such as historian Félix Luna, the Junta composition proposal shows such a level of balance among the relevant political and ideological parties involved that it can't be considered as merely the result of an improvised popular initiative.[95] The proposed President, Saavedra, have had a decisive intervention in the revolution and had prestige among all parties involved. Juan José Paso, Manuel Belgrano, Juan José Castelli and Mariano Moreno were lawyers influenced by the libertarian ideas, and the first three were former supporters of the Carlotist project. Juan Larrea and Domingo Matheu were peninsular Spaniards, involved in commercial activities of some importance. Both of them were supporters of Martín de Álzaga, as Moreno. Miguel de Azcuénaga was another military, with contacts among the high society, and the priest Manuel Alberti represented the aspirations of the lower clergy. Miguel Angel Scenna points in his book "Las brevas maduras" that "such balance could not have been the result of chance, or from influences from outside the local context, but of a compromise of the parties involved". Both authors deny the theory that claims that the composition of the Junta may had been suggested by the British: there was no time for that, nor there was any British in Buenos Aires important enough so as to influence in such matters.[96] Finally, the idea of the Junta being chosen by the military is also unlikely: despite the presence of Saavedra as president of the Junta, it wasn't a military Junta and the majority of its members were civilians. Even more, it included Mariano Moreno, whose stir with Saavedra dated from the failed mutiny of 1809.[97]

The Cabildo accepted the document, and moved to the balcony to submit directly to the people the ratification of the popular request. But given the lateness of the hour and the weather, the number of people in the plaza had declined. Leiva ridiculed the claim of the representation to speak on behalf of the people. This filled the patience of the few who were in the plaza, in the drizzle. Beruti did not accept any futher delays, and threaten to call people to arms. Facing the prospect of further violence, the popular request was read aloud and immediately ratified by the attendees. The rules governing the Junta were decided to be roughly the same as that issued the day before, with the additional provisions that the council would control the activity of the members of the Junta, and that the Junta itself would appoint replacements in case of vacancies. Then, Saavedra spoke to the crowd gathered under the rain, and then he moved on to the Fort, among salvos of artillery and the ringing of bells. Meanwhile, Cisneros dispatched José Melchor Lavin to Córdoba to warn Santiago de Liniers about what had happened in Buenos Aires, and demanding from him military action against the Junta.

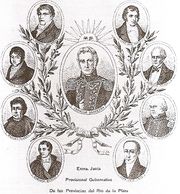

Members

The Primera Junta was composed as follows:

President

- Cornelio Saavedra

Voting members

- Dr. Manuel Alberti

- Col. Miguel de Azcuénaga

- Dr. Manuel Belgrano

- Dr. Juan José Castelli

- Domingo Matheu

- Juan Larrea

Secretaries

- Dr. Juan José Paso

- Dr. Mariano Moreno

Viewpoint of Cisneros

The deposed Viceroy Cisneros gave his version of the events of May week in a letter directed to King Ferdinand VII, dated June 22, 1810:

| “ | I had ordered a company to be at each intersection of the plaza so that anyone that was not invited would not be allowed to enter it, or to get into the Casas Capitulares. But the soldiers and officers were members of the (revolutionary) party, so they did what their commanders told them in private. They advised them to deny the entrance to the plaza to the honest neighbours and allow the conspiracy members into the City Council instead, as they had some blank official copies of the invitations they filled with the names of subjects unknown to the council, or because they were biased people, or because of the money. So, in a city of over three thousand distinguished and noteworthy residents only two hundred attended and, of those, there were many storekeepers, some craftsmen, other children of the family and the most ignorant and without the slightest notion so as to discuss a matter of the utmost gravity. | ” |

Aftermath

Neither the Council of Regency, nor the members of the Royal Court, nor the Spanish population from Europe believed the declaration of loyalty to the captive King Ferdinand VII to be true, so they were not willing to accept the new situation. The Real Audiencia de Buenos Aires refused to take the oath from the members of the Primera Junta. When they were forced into doing so, they did it with expressions of contempt. On June 15, members of the Royal Court secretly swore allegiance to the Council of Regency and sent communiqués to the rest of the cities of the Viceroyalty, calling them to deny recognition of the new government. To end these actions, the Junta convened all the members of the Audience, the Bishop Lue y Riega, and former Viceroy Cisneros, with the pretext that their lives were in danger, and shipped them into exile aboard the British ship Dart. Its captain, Mark Brigut Larrea, was instructed to avoid any American port and deliver all of them directly to the Canary Islands. Following this, a new composition for the Audience was appointed, entirely composed of Criollos loyal to the revolution.

With the exception of the city of Córdoba, every city in the territory of modern Argentina decided to endorse the Primera Junta. The cities of the Upper Peru, however, did not take a position, due to the recent outcomes of the Chuquisaca and La Paz Revolutions. Asunción del Paraguay rejected the Junta and swore loyalty to the Regency Council. The Banda Oriental, under Francisco Javier de Elío, remained a royalist stronghold.

Former Viceroy Santiago de Liniers led a counter-revolution in Córdoba, against which it was sent the first military campaign of the independent government. Despite the importance of Liniers himself, and his prestige as a popular hero for his role when the British invasions, the population of Córdoba preferred to support the revolution, and this sapped the power of the counter-revolutionary army by means of desertions and sabotage. Liniers troops were thus quickly smothered by the forces led by Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo. However, Ocampo refused to shoot the captive Liniers, who had fought alongside him in the British invasions, so the execution ordered by the Junta was carried on by Juan José Castelli.

After quelling this rebellion, the Junta proceeded to send military expeditions to many other cities, demanding support for the Primera Junta and the election of representatives to it. Military service was required to almost all families, both poor and rich, whereupon most of the patrician families chose to send their slaves to the army instead of their children. This is one of the usually stated reasons for the sudden decline of the black population in Argentina.

Montevideo, which had a historical rivalry with the city of Buenos Aires, opposed the Primera Junta and was declared the new capital of the Viceroyalty by the Regency Council, which appointed Francisco Javier de Elío as the new Viceroy as well. The city was well defended so it could easily resist an invasion, but the peripheral cities over the Banda Oriental acted contrary to Montevideo's will, and supported the Buenos Aires Junta. They were led by José Gervasio Artigas, who kept Montevideo under siege until the final defeat of the royalists.

The Captaincy General of Chile followed an analogous process to that of the May Revolution electing a Government Junta, that inaugurated the brief period known as Patria Vieja. However, the Junta would be defeated in 1814 at the battle of Rancagua, and the subsequent Reconquista of Chile would made it a royalist stronghold once more. Even so, the Andes mountain range provided an effective natural barrier between the Argentine revolutionaries and Chile, so there was no military confrontation between them until the Crossing of the Andes, led by José de San Martín in 1817. This campaign would signify the defeat of the Chilean Royalists.

The Primera Junta expanded to incorporate the representatives sent by the provinces. From then on, the Junta was to be known as the Junta Grande. However, it would be dissolved shortly after the June 1811 Patriot defeat at the Battle of Huaqui, and two successive triumvirates were to be elected to exercise the executive power of the United Provinces of South America. On 1814, the second triumvirate was to be replaced for the uni-personal authority of the Supreme Director, so as to enhance the executive action. Meanwhile, Martín Miguel de Güemes contained the royalist armies sent from Peru at Salta, while San Martín advanced towards the royalist stronghold of Lima by sea, on a Chilean-Argentine campaign, so the independence war gradually displaced towards northern South America. However, Argentina would contemporarily fall into a Civil War.

Consequences

According to historian Félix Luna's Breve historia de los Argentinos, one of the most important consequences of the May Revolution in society was the paradigm shift in the way the people and its rulers related. Until then, the conception of the common good prevailed: while the royal authority was fully respected, if an instruction from the crown of Spain was considered detrimental to the common good of the local population, it was to be half-met, or simply ignored. This was the usual procedure. With revolution, the concept of common good gave way to that of popular sovereignty, theorized by Moreno, Castelli and Monteagudo, among others: this idea held that, in the absence of a legitimate authority, the people had the right to appoint their own leaders. Over time, popular sovereignty would give way to the majority rule doctrine. This maturation of ideas was slow-paced and gradual, and it took many decades to crystallize in stable electoral and political systems, but it was what ultimately led to the adoption of the republican system as the form of government for Argentina. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento stated similar views in his Facundo, noticing that cities were more pervious to republican ideas, while rural areas were more resistant to them, leading to the surge of caudillo leaders.

Another consequence, also according to Luna, was the disintegration of the territories that once belonged to the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata in several different units. Most of the cities and provinces had distinctive populations, productions, attitudes, contexts and interests. Until then, all of these peoples were held together by the authority of the Spanish government, but with its disappearance, peoples from Montevideo, Paraguay or the Upper Peru began to distance themselves from Buenos Aires. The very short period of existence of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, barely 38 years, impeded a patriotic feeling to consolidate and bring a sense of community to all of its populations. Juan Bautista Alberdi sees in May Revolution one of the early manifestations of the power struggles between the city of Buenos Aires and the provinces, one of the axial conflicts at play in the Argentine civil wars. Alberdi wrote in his book "Escritos póstumos" the following:

| “ | The revolution of May 1810, done in Buenos Aires, that had to be meant only for the independence of Argentina from Spain, had also the consequence of emancipating the province of Buenos Aires from Argentina or, rather, to impose the authority of this province to the whole nation emancipated from Spain. That day, the Spanish power ended over the Argentine provinces, and it was established that of Buenos Aires.[98] | ” |

Historical perspectives

Historiographical studies of the May Revolution do not face many doubts or unknown details. Most important details about it were properly recorded at the time, and made available to the public by the Primera Junta as patriotic propaganda. Because of this, the different historical views on the topic differ on interpretations of the meanings, causes and consequences of the events rather than the accuracy of the depiction of the event themselves. The modern historical vision of the revolutionary events do not differ significantly from the contemporary ones.

The first people who wrote about the Revolution were most of the protagonists themselves of it, writing memories, biographies or diaries. However, their works were motivated by other purposes than historiographic ones, such as to explain the reasons for their actions, clean their public images, or manifest their support or rejection for public figures or ideas of the time.[99] For example, Manuel Moreno wrote the biography of his brother Mariano to use t as propaganda for the Revolution in Europe, and Cornelio Saavedra wrote his autobiography at a moment were his image was highly questionated, to justify himself before his sons.

The first remarkable historiographical school of interpretation of the history of Argentina was founded by romantic authors of the 1830 decade, like Bartolomé Mitre. Mitre regarded the May Revolution as an iconic expression of political egalitarianism, the conflict between modern freedoms and oppression represented by the Spanish monarchy, and the attempt to establish a national organization on constitutional principles as opposed to the leadership of the caudillos.[100] Their views were treated as canonical up to the ending of the 19th century, when the proximity of the Centennial encouraged authors to seek new perspectives. Such authors would differ about the weight of the causes of the May Revolution or whose intervention in the events was more decisive, but the main points made by Mitre were kept,[101] such as considering the revolution the birth of modern Argentina, and an unavoidable event.[102] They also introduced the idea of popular intervention as another key element.[103] By the time of the World Wars, liberal authors attempted to impose an ultimate and unquestionable historical perspective, though Ricardo Levene and the Academia Nacional de la Historia,[104] which kept most perspectives of Mitre. Left-wings authors opposed it with a revisionist production, based in nationalism and anti-imperialism, who minimized the dispute between criollos and peninsulars and explained instead a dispute between enlightenment and absolutism.[105] However, most of their work was focused at other historical periods.[105]

The May Revolution hasn't been the product of the actions of a single political party with a clear and defined agenda, but a convergence of sectors with varying interests. Thus, the number of conflicting perspectives about it is derived from which sector is chosen by each author to give the main focus or view with the higher detail.[106] Mitre would use The Representation of the Hacendados and the party of retailers to state that the May Revolution intended to obtain free trade and economic integration with Europe, right-wing revisionists would center around Saavedra and the social customs of the time to describe the revolution under conservative principles, and left-wing revisionists would resort to Moreno, Castelli and the rioters led by French and Beruti to describe it as a radical revolution.[107]

Revolutionary purposes

_by_Goya.jpg)

The government created on May 25 was pronounced loyal to the deposed Spanish king Ferdinand VII, but historians do not agree on whenever such loyalty was genuine or not. Since Mitre, many historians consider that such loyalty was merely a political deception to gain factual autonomy.[108][109][110] The Primera Junta did not pledged allegiance to the Regency Counsel of Spain and the Indies, an agency of the Spanish monarchy still in operation, and in 1810 the possibility that Napoleon Bonaparte was defeated and Ferdinand returned to the throne (which would finally happened on December 11, 1813 with the signing of the Treaty of Valençay) still seemed remote and unlikely.[111] The purpose of the deception would have been to gain time to strengthen the position of the patriotic cause, avoiding the reactions that may have led by a revolution, on the grounds that monarchical authority was still respected and that no revolution took place. The ruse is known as the "Mask of Ferdinand VII" and would have been upheld by the Primera Junta, the Junta Grande, and the First and Second Triumvirates. The Assembly of Year XIII was intended to declare independency, but failed to do so because of other political conflicts between its members; however, it suppressed mentions to Ferdinand VII from official documents. The supreme directors held an ambivalent attitude until the declaration of independence of 1816.

For Britain the change was potentially favorable, as it facilitated trade with the cities of the area without seeing it hampered by the monopoly that Spain maintained over their colonies for centuries. However, Britain prioritized the war in Europe against France, allied with the Spanish power sector that had not yet been submitted, and could not appear to support American independentist movements or allow military attention of Spain being divided into two different fronts. Consequently, they pushed for independence demonstrations not being made explicit. This pressure was exerted by Lord Strangford, the British ambassador at the court of Rio de Janeiro, expressing support to the Junta, but conditioned "...if the behavior is consistent and that Capital retained on behalf of Mr. Dn. Ferdinand VII and his legitimate successors."[112] However, the following conflicts between Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Artigas led to internal conflicts in the British front, between Strangford and the Portuguese regent John VI of Portugal.[112]

Since Juan Bautista Alberdi, later historians such as Norberto Galasso,[113] Luis Romero or José Carlos Chiaramonte[114] held in doubt the interpretation made by Mitre, and designed a different one. Alberdi thought that "The Argentine revolution is a chapter of the Hispanoamerican revolution, which is such of the Spanish one, and this, as well, of the European revolution."[115] They did not consider it a dispute between independentism and colonialism, but instead a dispute between the new libertarian ideas and absolutism, without the intention to cut the relation with Spain, but to reformulate it. Thus, it would have the characteristics of a civil war instead.[116] Some points that would justify the idea would be the inclusion of Larrea, Matheu and Belgrano in the Junta and the later appearance of José de San Martín: Larrea and Matheu were Spanish, Belgrano studied for many years in Spain, and San Martín had lived so far most of his adult life waging war in Spain against the French.[117] When San Martín talked about the enemies, he called them "royalists" or "Goths", but never "Spanish".

According to those historians, the Spanish revolution against absolutism got mixed with the Peninsular War. Charles IV was seen as an absolutist king, and by standing against his father many Spanish got the wrong understanding that Ferdinand VII sympathized with the new enlighten ideas.[118] Thus, the revolutions made in the Americas in the name of Ferdinand VII (such as the May Revolution, the Chuquisaca Revolution or the one in Chile) would have been seeking to replace the absolutist power with others made under the new ideas. Even if Spain was at war with France, the ideals themselves of the French Revolution (liberty, equality and fraternity) were still respected by those people.[119] However, those revolutions pronounced themselves enemies of Napoleon, but did not face any active French military attack, which promoted instead fights between Spanish armies for keeping the old order of maintaining the new one. This situation would have changed with the final defeat of Napoleon and the return of Ferdinand VII to the throne, as he restored absolutism and persecuted the new libertarian ideas within Spain. For the people in South America, the idea of remaining as part of the Spanish Empire, but with a new relation with the mother country, was no longer a feasible option: the only remaining options at this point would have been a return to absolutism, or independentism.

Legacy

May 25 is remembered as a patriotic date in Argentina, known as First Patriotic Government, with the character of a national holiday. The holiday is set by law 21.329 and it is immovable, meaning it is celebrated exactly on May 25 regardless of day of the week.[120] In the year 2010 will be 200 years of the May Revolution, leading to the Bicentennial of Argentina.

May 25 was designated as a patriotic day on 1813, but the Argentine Declaration of Independence provided an alternative national day. In the beginning, this added to the conflicts between Buenos Aires and the provinces in the Argentine Civil War, with the date on May being related to Buenos Aires and the 9 of July to the whole country.[121] This led the unitarian Bernardino Rivadavia to cancel the celebration on July, and the federalist Juan Manuel de Rosas to re-allow it, but without giving up celebrations on May. By 1880, with the federalization of Buenos Aires, the local connotations were removed and the May Revolution was considered the birth of the nation.[121]

The date, as well as the image of a Cabildo in a generic form, are used in different variants to honor the May Revolution. Two of the most notable are the Avenida de Mayo and the Plaza de Mayo at Buenos Aires, at the latter it was erected the Pirámide de Mayo a year after the revolution, which was rebuilt to its present form in 1856. "May 25" (in Spanish, "Veinticinco de Mayo") is the name of several administrative divisions, cities, public spaces and landforms of Argentina. There are departments under this name in the provinces of Chaco, Misiones, San Juan, Rio Negro and Buenos Aires, the later one holding the Veinticinco de Mayo city. The cities of Rosario (Santa Fe), Junín (Buenos Aires) and Resistencia (Chaco) have eponymous squares. The King George Island is under sovereignty claims of Argentina, Britain and Chile, as part of the Argentine Antarctica, British Antarctic Territory and Chilean Antarctic Territory; with Argentina knowing it as "Isla 25 de Mayo".

A commemorative Cabildo is also used at coins of 25 cents, and an image of the Sun of May on the 5 cents of the current Argentine Peso. An image of the Cabildo during the Revolution was also included the back of the back of banknotes of 5 pesos of the former Peso Moneda Nacional.

In popular culture

The nature of anniversaries of May 25 drives each year the description in children's magazines in Argentina, for example Billiken, as well as textbooks use in primary schools. These publications often omit some aspects of the historical event, as their violence or political content might be considered inappropriate for minors, such as the high arming of the population of that time (following the preparation against the second British invasion) or the class struggle between the Criollos and the Spanish peninsulares. Instead, it focuses on the revolution as an event devoid of violence and that inevitably would have happened one way or another, and the emphasis is on secondary issues such as the weather on 25 and if that day it rained or not, or whether the use of umbrellas was widespread or limited to a minority.[122] It is also presented as archetypal of the revolution the presence of various workers, including a mazamorreros delivering pies among the people in the plaza on May 25.

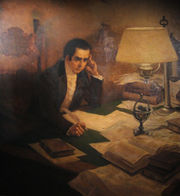

The Argentina Centennial led to the creation of many different works or representations. Chilean painter Pedro Subercaseaux created many related paintings after requests from Ángel Carranza, such as Cabildo abierto del 22 de mayo de 1810, Mariano Moreno writing in his desk, the embrace of Maipú between San Martín and Bernardo O'Higgins, or the first playing of the Argentine National Anthem. Such works would later become the canonical images about such topics.[123] The centennial also led to the production of La Revolución de Mayo, an early silent film, shot in 1909 by Mario Gallo and premiered in 1910. It was the first Argentine fiction film done with professional actors.[124]

Among the songs inspired by the events of May is the "Candombe de 1810". The tango singer Carlos Gardel sang "El Sol del 25", with lyrics by Domingo Lombardi and James Rocca, and "Salve Patria" by Eugenio Cardenas and Guillermo Barbieri. Peter Berruti, meanwhile, created "Gavota de Mayo" with folk music.

An analysis of the May revolution from the point of view of literary fiction is the 1987 novel La Revolución es un Sueño Eterno (The Revolution is an Eternal Dream), by Andrés Rivera. The narrative is based on the fictional diaries of Juan José Castelli, who had to endure trial for his conduct in the course of the disastrous First Alto Perú campaign. Throughout the fictional account of a mortally ill Castelli, Rivera criticizes the official history and the true nature of the revolution.[125]

The Bicentennial in 2010 produced fewer related works than the Centennial. Many related books were written close to it, such as "1810", "Enigmas de la historia argentina", "Hombres de Mayo" or "Historias de corceles y de acero".[126] The main filming production for the time is San Martín: El Cruce de los Andes, a movie based in the Crossing of the Andes performed by José de San Martín (another event of the Argentine War of Independence, but years after the May Revolution). The film, protagonized by Rodrigo de la Serna and produced by channels 7 and Encuentro, is scheduled to be released on May 25.

See also

- Primera Junta

- Argentine War of Independence

- Argentine Declaration of Independence

- History of Argentina

Bibliography

- Abad de Santillán, Diego (in Spanish). Historia Argentina. Buenos Aires: TEA (Tipográfica Editora Argentina).

- Belgrano, Manuel; Felipe Pigna (2009). Manuel Belgrano: Autobiografía y escritos económicos. Buenos Aires: Planeta. ISBN 978-950-043189-7.

- Brownson, Orestes (1972). American Republic. United States of America: College and University Press Services.

- Dómina, Esteban (2003). Historia mínima de Córdoba. Córdoba, Argentina: Ediciones del Boulevard. ISBN 978-987-556-023-9.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2002). The Napoleonic wars: the Peninsular War 1807–1814. Great Britain: Osprey Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84176-370-5.

- Galasso, Norberto (2005). La Revolución de Mayo (El pueblo quiere saber de qué se trató). Buenos Aires: Ediciones del pensamiento nacional. ISBN 950-581-798-3.

- Gelman, Jorge; Raúl Fradkin (2010). Doscientos años pensando la Revolución de Mayo. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3179-9.

- Heckscher, Eli (2006). The Continental System: An economic interpretation. New York: Old Chesea Station. ISBN 1-60206-026-6.

- Kaufmann, William (1951). British policy and the independence of Latin America, 1804–1828. New York: Yale Historical Publications.

- López, Vicente (1966) (in Spanish). La gran semana de 1810. Buenos Aires: Librería del colegio (sic).

- Luna, Félix (1994) (in Spanish). Breve historia de los argentinos. Buenos Aires: Planeta / Espejo de la Argentina. 950-742-415-6.

- Luna, Félix (2001). Grandes protagonistas de la Historia Argentina: Juan José Castelli. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Planeta. ISBN 950-49-0656-7.

- Luna, Félix (2004). Grandes protagonistas de la Historia Argentina: Manuel Belgrano. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Planeta. ISBN 950-49-1247-8.

- Luna, Félix (2004) (in Spanish). Grandes protagonistas de la Historia Argentina: Mariano Moreno. Buenos Aires: La Nación. ISBN 950-49-1248-6.

- Luna, Félix (1999) (in Spanish). Grandes protagonistas de la Historia Argentina: Santiago de Liniers. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Planeta. ISBN 950-49-0357-6.